- Key Takeaways

- The Interlocking Gears

- A Cosmic Blueprint

- Weaving Prophecy

- The 2012 Myth

- A Living Tradition

- Modern Resonance

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Key Takeaways

- The Maya calendar system, comprising the Tzol’kin, Haab’, and Long Count, interlocked to keep time for short cycles and long historical periods.

- These calendars influenced agricultural cycles, ritual ceremonies, and everyday decisions, reflecting the profound integration of timekeeping into Maya culture.

- Astronomical observations were key to calendar calculations, enabling the Maya to align rituals and farming with natural cycles.

- The calendar was used for prophecy and divination, with daykeepers decoding dates to direct social and religious life.

- The 2012 date was the conclusion of a single Long Count cycle — not an apocalypse — and our contemporary misunderstandings have obscured the reality of its cultural significance.

- Maya communities today preserve and practice these calendrical traditions, sustaining their legacy for generations to come.

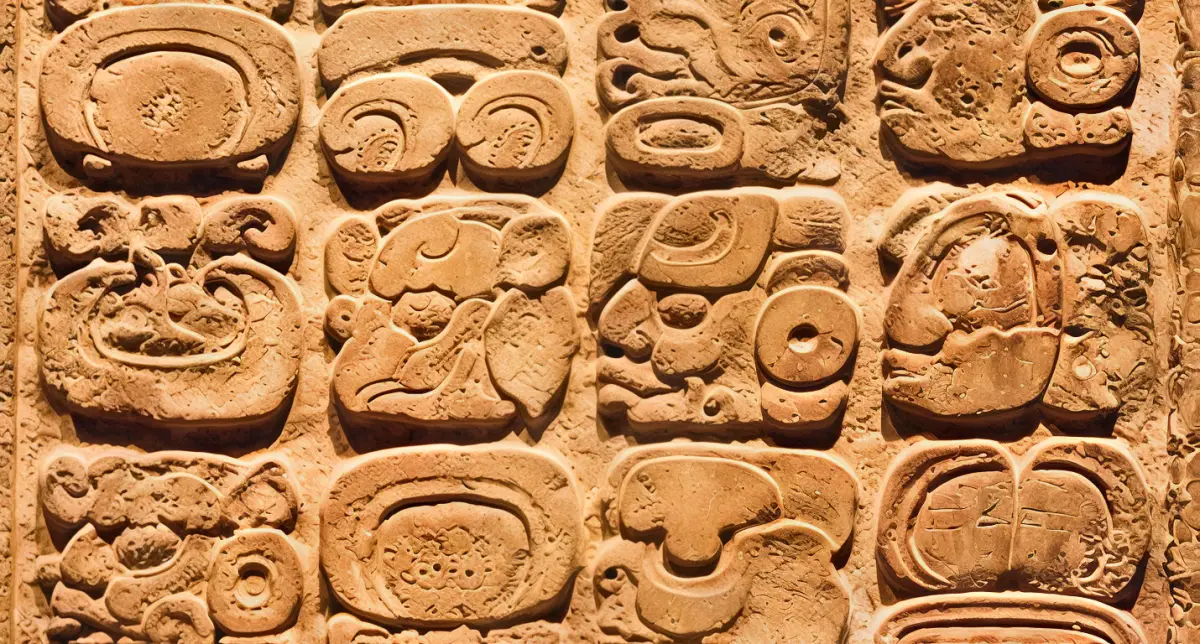

The Maya calendar system is a set of calendars used by the ancient Maya civilization to track time. Including the Long Count, Tzolk’in, and Haab’ cycles, each with its own unique method of denoting days and years. These calendars helped guide Maya farming, rituals, and daily life. The Tzolk’in is 260 days, but the Haab’ is 365 days, quite close to the year. The Long Count tracks longer cycles, allowing Maya peoples to record dates over thousands of years. Symbols and glyphs were used to record dates, making the system distinctive and sophisticated. To provide a good sense of their timekeeping methods, the main text dissects each Maya Calendar System and its applications.

The Interlocking Gears

The Maya calendar system was unique in its complexity, and in the way its three main components—Tzolk’in, Haab’, and Long Count—interlocked like gears. These ancient Maya calendar systems helped the Maya people track time for daily life, farming, ceremonies, and history, reflecting their belief that time is cyclical rather than linear.

1. The Tzolkin

The Tzol’kin, or sacred calendar, runs for 260 days and is based on two repeating cycles: twenty named days and thirteen numbers. Each day is named and numbered, creating 260 combinations in a full cycle, which ties to the human gestation period and the corn staple central to Maya life. Each day in the Tzol’kin has a god associated with it, influencing the daily cadence of work, ritual, and choice. The ancient Maya applied the Tzol’kin to divination, reading the fate of a person based on the Maya date of their birth. This intricate system of interlocking gears ensures each date and digit snaps into place until the cycle repeats, a practice that persists among modern Maya groups in Guatemala to this day.

2. The Haab

The Haab’ calendar is the solar calendar used by the ancient Maya, consisting of 18 months of 20 days, plus five additional “Wayeb’” days that were considered to be unlucky. This Maya calendar system scheduled farming and social events, ensuring that community life remained in tune with the seasons. Together with the Tzol’kin, these cycles form the Calendar Round, which repeats every 52 years, or 18,980 days — a generation — reflecting a common temporal culture. This time was significant, as the turning of the year signified rebirth and the necessity of special rites to maintain ongoing cosmic order.

3. The Calendar Round

The Calendar Round interlocks the Tzol’kin and Haab, creating 18,980 unique days before cycling back, showcasing the sophisticated calendar systems of the ancient Maya. It was a society-organizing system that recorded birthdays, anniversaries, and significant events, embodying the Mayan understanding that time is cyclical, never linear. With the Calendar Round used to time rituals and community ceremonies, everyone knew when to celebrate.

4. The Long Count

The Long Count, a vital aspect of the Mayan civilization, kept score of much longer stretches of time. It comprised 13 “baktuns,” each spanning roughly 400 years. This system begins on August 11, 3114 BC, a date deeply intertwined with Maya creation myths. The alleged “end” on December 21, 2012, was not the end of time but merely the conclusion of one cycle and the beginning of another. The Long Count allowed the Maya people to accurately record dynastic and historical events, showcasing their commitment to documenting their own place in history.

A Cosmic Blueprint

The Maya calendar system was a precise system, in fact, off by only a day in 6729 years — better than our current Gregorian calendar. Far more than a means of marking time, this calendar was a nexus of astronomy, daily life, and culture — a cosmic blueprint that helped shape Maya civilization.

-

Maya astronomers observed the heavens and charted the positions of the sun, moon, and planets. They leveraged these observations to calibrate their calendars, aligning the cycles with actual happenings. As an example, the Haab, a solar calendar of 365 days, corresponded to the solar year, whereas the Tzolk’in, 260 days, tracked spiritual and practical occurrences. The interlocking of these two cycles, with each Haab month always starting on the same Tzolk’in day, demonstrates their attentiveness in connecting time to nature’s cycles.

-

The calendar was important in farming and rituals. Farmers harnessed it to understand when to sow and reap– the optimal points in the annual cycle. Ceremonies and festivals were assigned to calendar dates, assisting people in revering the gods and tracking important junctures of the year, such as solstices or rain times. It was these links to nature that made the calendar such a vital survival and community tool.

-

The calendar, too, formed identity among the Maya. The Tzolk’in’s 260 days, constructed from 20 named days and 13 numbers, imbue each day with its own characteristics. The day of birth, affiliated with one of 20 day signs, was believed to guide a person’s journey—providing a ‘cosmic blueprint’ for their characteristics and fate. This concept still flourishes among Maya communities, who utilize the calendar for naming, astrology, and marking life’s milestones.

The Maya calendar’s connection to both the nine-month human gestation period and its continued use today speaks to its cosmic and earthly origins.

Weaving Prophecy

For the Maya, their calendar systems were not merely a way of keeping time; they molded the worldview and life planning of its readers. This concept of “weaving prophecy” connects to how the ancient Maya employed their calendar for prophecy and divination. Most are familiar with it from the 2012 effect. A few speculate that the final entry on the Maya calendar, 21 December 2012, would entail the apocalypse or some great transformation. This notion was popularized by Terence McKenna, who connected it with his “novelty theory” following psychedelic use. Scientists, however, dub novelty theory pseudoscience. Most researchers today think the Maya employed their calendar to connect past, present, and future, not to designate a single apocalyptic day.

There are many cycles to the Maya calendar, including the Tzolk’in days and the Haab cycle. The Tzolk’in has 20 named days and numbers 1 to 13, resulting in 260 unique days. These cycles intertwine and overlap, allowing modern Maya daykeepers to discover special meanings for each date. Daykeepers, or “aj k’ij,” were calendar-reading professionals who learned how to align each day with its distinct power and significance. Their primary role was to guide their communities, providing counsel on when to sow, conduct rituals, or discern individual destinies based on the calendar.

Calendar dates and prophecy were intricately linked to major events in Maya life. The calendar would record when a new leader was to come to power, when to build or bless a house, and when festivals were to be held. Daykeepers consulted the calendar to verify whether a date was lucky or risky. If a date coincided with a previous event, it was treated as a harbinger of a repeat occurrence. Thus, prophecy influenced decisions concerning war, peace, and commerce, becoming woven into everyday existence and politics itself. The “weaving” concept refers to the cyclical nature of time and human life, rather than a linear one. The calendar not only divined the future; it oriented the Maya people within the stream of time.

The 2012 Myth

All the hype around the Mayan calendar and the year 2012 resulted in many misconceptions about what the ancient Maya actually thought. Most of the world believed that the Maya foresaw the apocalypse on 21 December 2012, stemming from the conclusion of a 5,126-year cycle in the Maya Long Count calendar. This date marked the end of 13 b?ak?tuns, a period that was sacred to the Maya people. Nothing in Maya writing or on their monuments provides evidence that this date was connected to any disaster or apocalypse-type occurrence. Mayan scholars and archaeologists agree: Maya texts do not warn of doom or chaos at the end of this cycle. Instead, the conclusion of the 13th b?ak?tun was a moment of renewal, akin to the beginning of a new century.

The truth about the significance of the Long Count’s end lies in the rich traditions of the Maya and their calendar systems. This brings us back to the Long Count ‘zero date,’ 11 August 3114 BC, which symbolizes a new beginning following the conclusion of the third world. Ending a Great Period, such as 13 b?ak?tuns, was a significant event, much like a millennium to many cultures. The Maya system of calendars didn’t end there; they measured time in various systems, such as the Tzolk’in (260 days) and the Haab (365 days), reflecting a nuanced understanding of cycles and continuity, rather than closure.

Contemporary media was instrumental in propagating the 2012 doomsday myth. Numerous news sources, books, and movies claimed the Maya foretold disaster, despite having no foundation in either Maya history or science. The doomsday theories were scoffed at by the scientific community as pseudoscience. Astronomers noted that none of the suggested catastrophes—rogue planets, solar flares—were backed by actual evidence. Other Mayanists, like Stephen Houston, emphasized that future dates on Maya monuments were as much about forging connections to the past as ending.

The Mayan calendar remains revered today. It continues to be a living part of the Maya legacy and stands as a testament to a civilization that lived in harmony with nature and the rhythms of time.

A Living Tradition: The Maya Calendar System:

The Maya calendar is more than an artifact. In many Maya villages, it continues to influence everyday living, religious observance, and even agriculture and ritual scheduling. The Tzolk’in, a 260-day cycle created by overlapping 13- and 20-day cycles, remains in use for selecting days for ceremonies, sowing, and life events. The Haab, the solar component of the system, aids in defining seasons and directing labor in the fields as well as times for festivals. In highland villages, local year-bearer patterns are associated with certain boundary markers and mountains, demonstrating the way the calendar links the land, its people, and their common narrative.

For much of the region, the Maya calendar is central to agriculture and social life. Here are some ways it plays a role in modern times:

- Farmers consult the calendar to determine when to plant and harvest crops, aligning vital labor with opportune moments in the cycle.

- Communities mark pivotal moments, such as the month of Wayeb, when special attention is paid to rites of safeguarding and gratitude.

- Numerous villages organize festivities and festivals around dates from the calendar, maintaining old traditions and uniting people.

- The year-bearer pattern provides a beat for public events, and is associated with local landmarks; thus, the calendar becomes a map for social life.

Maintaining the tradition is hard work. Several Maya communities have initiated initiatives to educate youth in the calendar, imparting knowledge of its significance, symbols, and applications. Some provide courses, others conduct open rituals to demonstrate how the system integrates into everyday life. Pride in sharing these traditions is increasing as well, both among the community and with outsiders. That keeps the calendar robust, as the world changes.

The calendar is more than a counting device. For some, it’s a living tradition — a connection to their ancestors, a navigational system for understanding the world. With the calendar, they maintain a living tradition. They manage to do it all while still addressing the demands of contemporary life.

The Maya Calendar System Modern Resonance

Modern resonance is when a system aligns its intrinsic frequency with an external source, allowing it to efficiently capture and transfer energy. In physics, this phenomenon occurs when a swing reaches a higher height if you push it just so. This concept applies across many disciplines today, from constructing solid bridges to creating crisp images in medical scans. From circuits to musical instruments to molecules, resonance allows energy to travel cleverly. Sometimes, if builders don’t account for resonance, it can create damage or failure in machines and buildings. So, design and control matter.

The Maya calendar system is intriguing because it operates somewhat like this concept of resonance. The Maya measured time in cycles that were in harmony with nature. These cycles, such as the 260-day Tzolk’in or 365-day Haab’, coincide with the sun, moon, and seasons. As modern scholars observe, this path to counting time allows individuals to perceive rhythms and connections in both the natural and human worlds, as if the calendar itself “resonated” in harmony with the world. This is what makes the Maya calendar a bridge, allowing ancient Maya insights to inform fresh perspectives on time and transformation.

-

Researchers continue to gaze at Maya calendars to understand how ancient cultures perceived cycles, not merely as dates, but as living systems connected to earth and stars.

-

Recent research is employing computer models to verify how Maya cycles correspond to astronomy, climatology, or even agricultural rhythms.

-

Others collaborate with local Maya communities, connecting ancient calendar traditions to contemporary life, schooling, and even parties.

-

Fans and geeks maintain the flame, hosting public lectures, art exhibits, or web discussion boards broadcasting calendar trivia.

-

Museums and schools around the globe conduct programs to educate about Maya calendars, indicating that the fascination is anything but waning.

Artists draw inspiration from Maya calendar symbols in their paintings, digital art, music, and dance. By blending calendar glyphs, cycle shapes, and storytelling themes, these works span diverse cultures. The rhythms of the calendar help us see time from a new perspective or reflect on how the past influences the present. Its significance is evident in tattoo art, jewelry, stage design, and even graphic novels.

Conclusion about The Maya Calendar System

The Maya calendar system reveals profound mastery and reverence for time. Its rhythms, connections, and codes ring pure still. Humans take advantage of its rhythms for agriculture, scheduling, or commemorating holidays. Ancient legends, such as 2012, garnered headlines but didn’t alter the essence. The system still assists some folks nowadays. The Maya way mixes sun, moon, and stars with the cadence of life. From monitoring crops to planning events, the calendar remains durable. Its blend of math and narrative entices a lot of people to explore deeper. To understand what it’s like to live in a frame, ask someone who does or read on. Keep questioning, keep exploring–there’s a lot more to discover in this ancient but vibrant system.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Maya calendar system?

It utilizes multiple overlapping cycles, such as the Haab’, Tzolk’in, and Long Count calendars, integral to ancient Maya, to count days, months, and extensive time spans.

How do the Maya calendars interlock?

The Haab’ (365 days) and Tzolk’in (260 days) cycles gear together like cogwheels. Interlacing these cycles produces a Calendar Round of approximately 52 years, allowing the ancient Maya to navigate the stream of time with impressive accuracy.

What was the purpose of the Maya calendar system?

The ancient Maya calendar system assisted the Maya peoples in structuring everyday life, agriculture, religion, and prophecy, providing a cosmic blueprint for time and the universe through its intricate calendar systems.

Did the Maya calendar system predict the end of the world in 2012?

No, the Maya calendar 2012 did not signify the end of the world; rather, it marked the end of a cycle (the 13th baktun) and the beginning of a new cycle in the ancient Maya tradition.

Is the Maya calendar still used today?

Indeed, certain Maya communities continue to practice calendar ceremonies and cultural events, reflecting the enduring traditions of the ancient Maya in some areas of Central America.

How did the Maya use their calendar for prophecy?

The ancient Maya would use their calendar systems to direct ceremonies, foresee events, and select lucky dates, shaping social, religious, and political decisions.

What is the Long Count calendar?

The Long Count, a key aspect of the ancient Maya calendar systems, counts days from a fixed start date to track longer periods.